Education and advocacy

This page contains models and strategies for driving adoption of best practices throughout a development culture.

- Sell, don’t tell

- Abandon data and absolute reason

- Everything is not for everyone

- Crossing the chasm

- The Chasm

- “Poor quality” code not an issue

- Case study: Google’s Testing Grouplet

- Seize the teachable moments!

- Play the long game

Sell, don’t tell

By selling people on the value of an idea—i.e. by soliciting their “buy-in”—you give them the opportunity to feel ownership of it. In contrast, asserting authoritah makes people feel owned, like cattle, and fosters nothing but resentment, resistence, and ultimately rejection—even if the idea was likely a good one to begin with.

In other words, just as you would when selling a product or service, apply customer-first thinking to those you hope to persuade to make a change. Only from this mindset does an optimal product or solution emerge.

Abandon data and absolute reason

Best practices are often more about avoiding visible impact than producing it. Such negative impact is practically impossible to prove. Hence, when it comes to driving adoption of best practices, in general, experience is the most effective form of persuasion.

Given the distribution of the diffusion of innovations model, it’s inevitable that some will attempt to thwart your efforts to promote certain practices by demanding data proving its effectiveness. Disregard those who protest in this way: A demand for data proving the effectiveness of automated testing is cowardice masquerading as reason.

Alternatively, turn the argument around: Ask for the data that conclusively made the case for using programming language X, or text editor Y, or hosting platform Z.

Everything is not for everyone

Taking Test-driven development (TDD) as an example, the end result is well-tested code. TDD is not the only means to get there. The goal is to promote best practices that people perceive as having value based on their own experience rather than coersion or academic purity.

Crossing the chasm

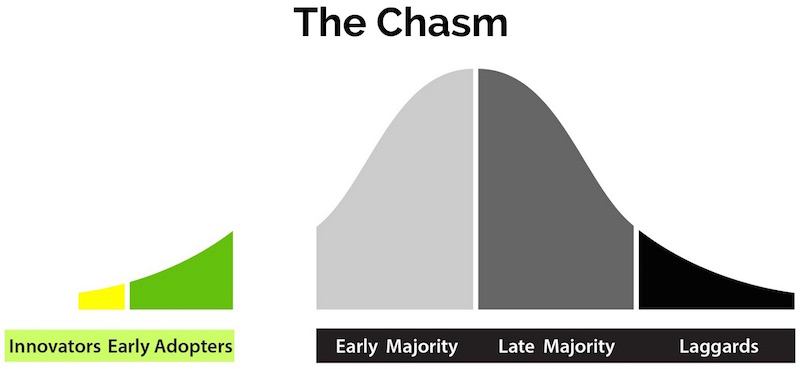

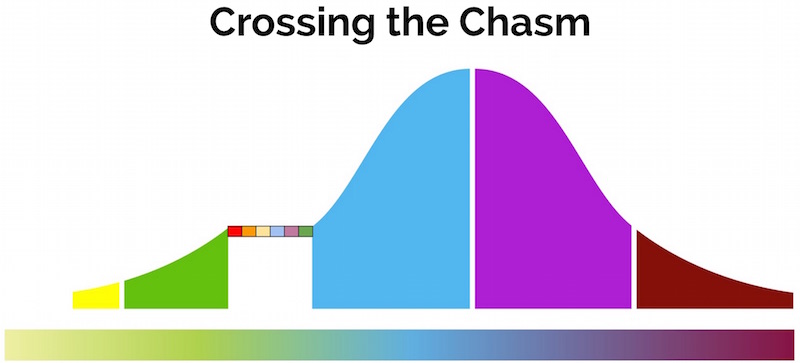

Geoffrey A. Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm first explains the different segments of the bell curve-shaped diffusion of innovations model:

Image by Catherine Laplace based on other illustrations of the “Crossing the

Chasm” model.

- Innovators and Early Adopters: Partners-in-crime, believe in principle, help each other clarify concepts, principles, priorities.

- Early Majority: Persuaded by results, reason, positive experience.

- Late Majority: Persuaded by common practice, lack of friction.

- Laggards: Abandon them. They’re useless, dead weight.

The Innovators and Early Adopters comprise the Instigators. It’s their responsibility to cross the “chasm” identified by Moore as the gap between the Early Adopters and the Early Majority. Crossing the Chasm is what determines the success or failure of an initiative, as crossing it is necessary to achieve widespread adoption.

The Chasm

Using automated testing adoption as an example, the “chasm” may be characterized as:

- Slow and/or incorrect builds

- Ignorance of principles, techniques, and idioms

- Poor management and development culture

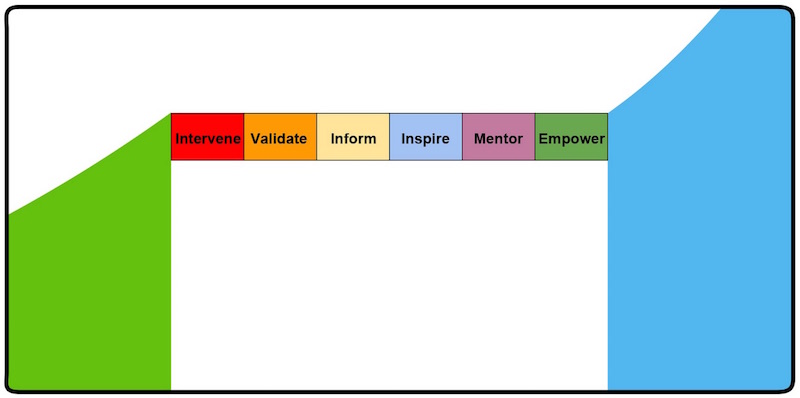

The chasm is best crossed via persuasion, not force (laggards notwithstanding). The Rainbow of Death model describes a progression of activities Instigators must undertake to lead the Early Majority across the chasm.

Images by Catherine Laplace based on other illustrations of the “Crossing the

Chasm” model and Albert Wong’s framework image.

Fulfilling each step is necessary to producing lasting, positive change. By moving from one step to the next (conceptually; in reality many efforts must happen in parallel), the Early Majority is transformed from Dependent upon the Instigators to Independent:

- Intervene: Instigators do the work.

- Validate: Instigators validate the efforts of the Early Majority.

- Inform: Instigators provide technical information and training to the Early Majority.

- Inspire: Instigators motivate the Early Majority and help them feel that their work is valuable.

- Mentor: Instigators build strong relationships with Early Majority members.

- Empower: Early Majority members are able to do the work, with ongoing support from Instigators.

“Poor quality” code not an issue

“Poor quality” code is not part of the chasm. It’s a symptom, not a cause. Spread ideas and remove obstacles, and the code will improve.

Case study: Google’s Testing Grouplet

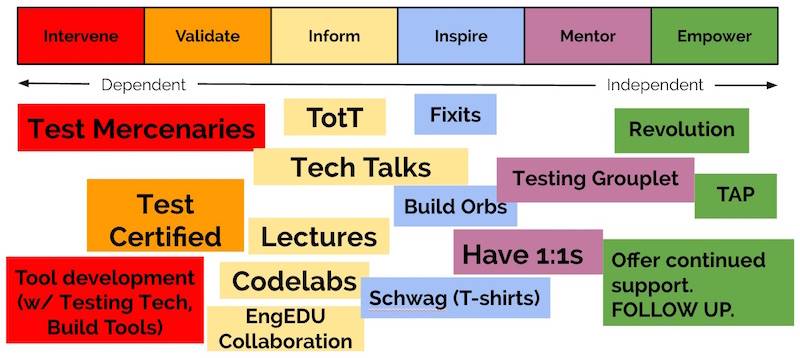

Google’s Testing Grouplet was a team of volunteers pooling their 20 percent time to drive adoption of automated developer testing, in the most serious and fun ways possible. Some of the more significant efforts included:

- Test Certified: a concrete roadmap towards sound automated testing.

- Testing on the Toilet: a weekly, one-page flyer published in restrooms company-wide to introduce testing concepts and tool developments. Started in 2006 and still running today (January 2015), it proved a fantastic, distributed volunteer task. It started and standardized conversations, both inside and outside the Testing Grouplet, avoiding the echo chamber effect.

- Test Mercenaries: hands-on internal consultants that helped teams move up the Test Certified ladder. They also both informed internal tool development and drove company-wide tool adoption.

- Fixits: limited-time, all-out efforts to address “important but not urgent” tasks and roll out new tools. Fixits built momentum and morale, and the focused effort overcame huge obstacles, setting the stage for future developments.

This is how these efforts and a few others fit into The Rainbow of Death model:

Derived from Albert Wong’s original framework slide from a Google-internal

tech talk.

Seize the teachable moments!

“goto fail” and Heartbleed were prime examples of why unit testing is so critical. Both bugs were unit-testable, as proven by the working code in the Finding More Than One Worm in the Apple and Goto Fail, Heartbleed, and Unit Testing Culture articles.

When such opportunities to demonstrate the importance of best practices arise, we can seize the chance to publish articles, give presentations, and refer to existing works. Such activities build a body of knowledge and give our arguments scholarly weight.

When making our arguments, it’s important to emphasize “why” we follow a practice as well as “how.” The “why” may be obvious to the Instigators who already “get it” but not necessarily to everyone.

Play the long game

Lasting change never comes quickly. Understand that the problem isn’t purely technical, and it isn’t just about the value of a particular practice. It’s about the “chasm”. Hearts and minds must be persuaded (Early Majority), won (Late Majority), or conquered (laggards).